Most existing PoS (Proof of Stake) blockchains use a BFT (Byzantine Fault Tolerant) consensus protocol that assumes a 33% (or 1/3) malicious validator threshold and requires two vote rounds (plus one proposal round, so three message rounds total) to reach finality. Recently, there has been renewed interest in one-vote-round BFT consensus (two message rounds total) under a 20% malicious validator threshold, such as Alpenglow, ChonkyBFT (zkSecurity's audit), and Minimmit. These two-message-round protocols usually achieve faster finality, especially when validators are geographically distributed and network latency dominates (here, a message round is a one-way broadcast phase, not a network round trip). This blog post explains the intuition behind one-vote-round BFT protocols and explores the idea of optimistic one-vote-round finality.

We will build intuition for questions like:

- Why do most existing PoS consensus protocols assume a 33% malicious bound (and not something like 50%)?

- Why do these BFT protocols usually require two rounds of voting?

- When, and why, is one round of voting actually possible?

- Why is optimistic one-vote-round BFT consensus useful?

The Basis

Let's start with the basic setting in BFT consensus. A set of validators (total n) collaborate to broadcast and finalize blocks. They communicate over a network that is not always stable, and some validators (total f) may behave maliciously (called Byzantine in the literature). BFT consensus aims to correctly finalize blocks despite both network uncertainty and faulty participants.

Network model. In the real world, the network is fast and stable most of the time. However, sometimes it can be unstable: messages can be delayed or lost, and network partitions can occur. For example, in the average case you might expect a computer in Tokyo to deliver a message to a server in New York City in 200ms. But if your router goes down or a submarine cable is cut, the network can become temporarily unreachable. This is often modeled as a partially synchronous network:

The network is asynchronous at the beginning and there is no bound on message delay. After some unknown time (GST, Global Stabilization Time), the network behaves synchronously and there is a known bound on message delay, but the protocol does not know when GST occurs.

Because GST is unknown to validators, they can never be sure whether the network is currently synchronous. Even if the network seems healthy, it could become disrupted in the next second. As a result, while the consensus algorithm is running, it has to always be safe under asynchrony.

Validator model. The majority of validators are honest: they follow the protocol and do not deviate arbitrarily (e.g., they never equivocate or double-vote). When an honest validator finalizes/commits a block, it treats that decision as irreversible and will only build on top of the finalized history. Some validators can be faulty in two ways:

- Crash faults: the node may stop responding but does not behave arbitrarily. This can happen if the validator crashes or becomes disconnected. When it comes back online, it will still follow the protocol and will not behave maliciously (e.g., it will not double-vote).

- Byzantine faults: the node may behave arbitrarily, including staying silent, equivocating, or double-proposing/double-voting.

A BFT consensus protocol should be resilient enough to maintain both safety and liveness under partial synchrony with Byzantine validators:

- Safety: all honest validators eventually finalize the same sequence of blocks. In other words, if an honest validator follows the protocol and commits/finalizes a block, other honest validators will also commit/finalize exactly the same block in that slot.

- Liveness: during synchrony, the protocol makes progress and does not get stuck.

Safety ensures no forks can occur even during asynchrony. Liveness requires it to make progress during synchrony.

Here is how BFT consensus in a PoS blockchain usually works at a high level: there is a fixed validator set, and each validator has stake-based weight. For simplicity, we assume equal stake. All messages between validators are authenticated with digital signatures to prevent forgery.

Time is divided into slots, and each slot has a designated leader known ahead of time (e.g., round-robin). In each slot, the leader proposes a block and broadcasts it to all validators. Other validators verify the proposal and broadcast their votes. Each validator only votes for the first valid proposal it receives in each slot. If a validator collects enough votes, it commits/finalizes the block and moves to the next slot. In future slots, a validator only votes for proposals that extend its highest finalized block, so it never builds on a fork that would conflict with finalized history. In case of a silent leader, if no block is finalized before a timeout, each validator broadcasts a timeout message, regardless of whether it voted in that slot. Once a quorum of timeouts is reached, validators move to the next slot.

The 33% Bound

Most existing PoS blockchains assume a 33% Byzantine threshold and require two vote rounds to finalize blocks. This is because 1/3 is (informally) the largest Byzantine fraction under which a partially synchronous BFT protocol can simultaneously maintain safety and liveness. Let's see why.

Let n be the total number of validators, of which at most f are Byzantine.

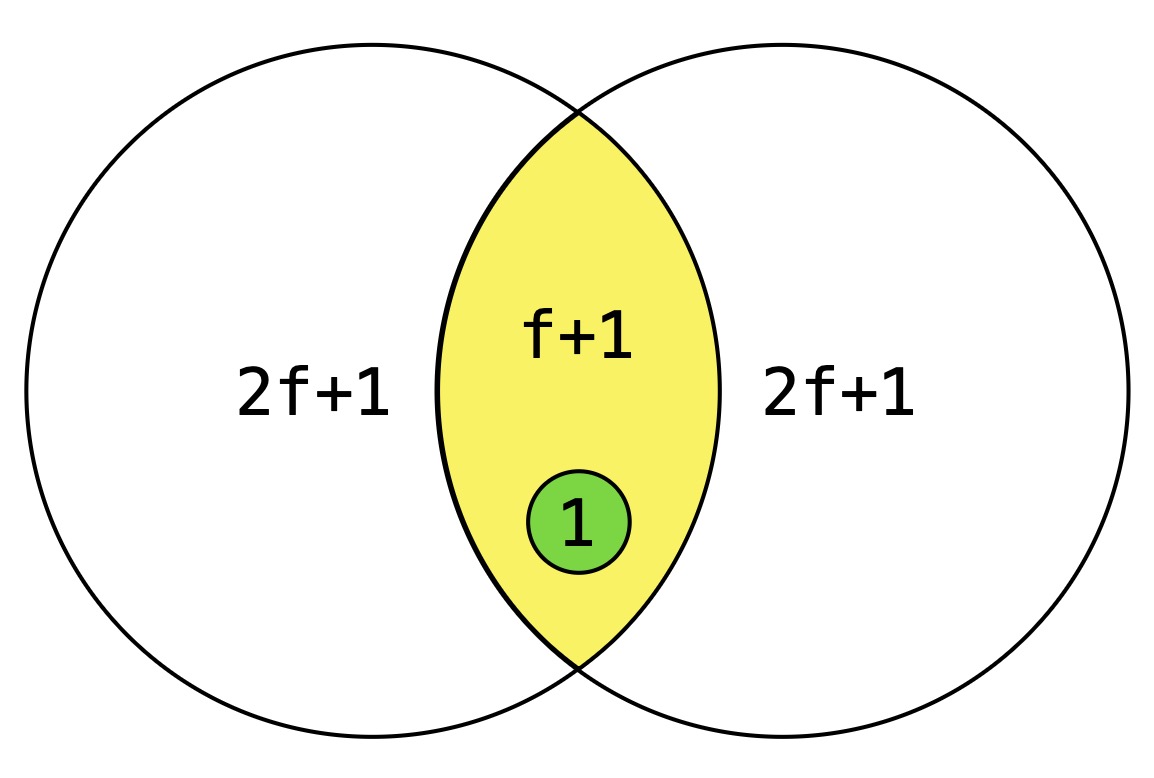

First, we introduce a useful analysis technique called quorum intersection: for two sets each with x validators, they have at least max(0, 2x - n) validators in common. Since at most f of those common validators can be Byzantine, the two sets have at least max(0, 2x - n - f) honest validators in common. For example, suppose n = 3f + 1 and we have two sets with x = 2f + 1 validators. Then the two sets overlap in at least f + 1 validators, and at least 1 of those must be honest. If two conflicting proposals each get 2f + 1 votes in a slot (so both reach quorum), then their vote sets must overlap in at least one honest validator, meaning some honest validator would have had to vote for both, which is impossible.

Now suppose a consensus algorithm needs votes from x validators to make a meaningful decision (i.e., the quorum is x). Recall that Byzantine validators can stay silent or equivocate.

- Liveness requires the protocol to be able to finalize using only honest votes even if all

fByzantine validators remain silent. In that worst case, onlyn - fvalidators are available, so we must havex ≤ n - f. Otherwise, if we setx = n - f + 1(or larger), then an adversary can mount a trivial DoS: keep all Byzantine validators silent, and the protocol will be perpetually "one vote short" of quorum and never make progress. - Safety requires that two conflicting decisions cannot both be reached even if all

fByzantine validators double-vote. To ensure that at most one proposal can reach quorum in a slot, we need the quorum to be large enough that any two quorum sets share at least one honest validator. That is:2x − n - f > 0, i.e.,x > (n + f) / 2. In this case, if two different proposals both getxvotes, then there must exist an honest validator that voted for both proposals, which is impossible.

Combining both directions, we need:

$$ (n + f) / 2 < x \le n − f $$For such an x to exist, we need:

That is exactly the statement that Byzantine validators must be less than one third of the total!

Intuitively, 1/3 is the largest Byzantine fraction where we can choose a quorum large enough to force honest overlap (safety) yet small enough to be reachable with only honest votes (liveness). This is why many PoS blockchains assume a 33% Byzantine threshold: it is the maximum resilience bound they can target.

The minimal integer choice is n = 3f + 1. In this classic setting, picking x = 2f + 1 satisfies both sides:

- Liveness:

2f + 1 ≤ n − f = 2f + 1. - Safety:

2x − n = (4f + 2) − (3f + 1) = f + 1 > f.

In this setting, if block B1 and a conflicting block B2 both receive 2f + 1 votes among 3f + 1 validators, their vote sets must overlap by at least f + 1. With at most f Byzantine validators, at least one overlapping voter is honest, implying an honest double-vote, which is impossible. So two conflicting blocks cannot both reach 2f + 1.

Note that 1/3 is the maximum threshold. We can, of course, assume a lower threshold such as n = 5f + 1 (i.e., 20%) when designing a protocol. In that case, all x in the range 3f + 1 ≤ x ≤ 4f + 1 are valid quorums. As we'll see, a lower Byzantine threshold is the key to reducing two vote rounds to one.

Two Voting Rounds

At first sight, it seems we only need one vote round when n = 3f + 1: in each slot, the leader proposes a block, validators validate it, broadcast a vote, and any validator that collects 2f + 1 votes immediately finalizes the block. This looks safe within a single slot because no conflicting block can reach 2f + 1 votes in that same slot. However, the block can still be "lost" if the slot times out.

Consider this scenario: all f Byzantine validators are silent. 2f honest validators vote for block B. The last honest validator also votes for B and locally sees 2f + 1 votes, so it finalizes B. But due to network asynchrony, it fails to deliver its vote to the rest. As a result, other validators never learn that B reached 2f + 1 votes. When the slot times out, the next leader can propose a block that skips B. In this case, one honest validator commits B while the others skip it. Safety is violated. The issue is that 2f + 1 votes only guarantees that B is the only candidate that could be committed in that slot, but it does not guarantee that the slot won't be skipped.

We add a second voting round to further decide whether the slot outcome is "commit B" or "empty" after the first round (inspired by this blog post):

- First vote (

vote1): after a validator sees the leader's proposalBand deems it valid, it broadcastsvote1(B). - Second vote (

vote2): if a validator observes2f + 1vote1for a blockB, it broadcastsvote2, which contains thevote1(B)it collected. After receiving2f + 1vote2, the validator commits blockBand moves to the next slot. - Timeout (

timeout): if a validator hasn't committed a block in this slot after a timeout, it broadcaststimeout. If the validator has sentvote1orvote2, it includes them in the timeout message:timeout(vote1, vote2). On seeing2f + 1timeoutmessages, a validator moves to the next slot.

If an honest validator committed a block, then it must have seen 2f + 1 vote2. By quorum intersection, any set of 2f + 1 timeout messages must intersect any set of 2f + 1 vote2 messages in at least one honest validator. This means that if the next leader collects 2f + 1 timeout, at least one of those timeout messages contains a vote2, which in turn contains 2f + 1 vote1. Therefore the block from the previous slot cannot be "lost": the protocol can require the next leader to extend it, and honest validators will refuse to vote for proposals that do not extend the locked block.

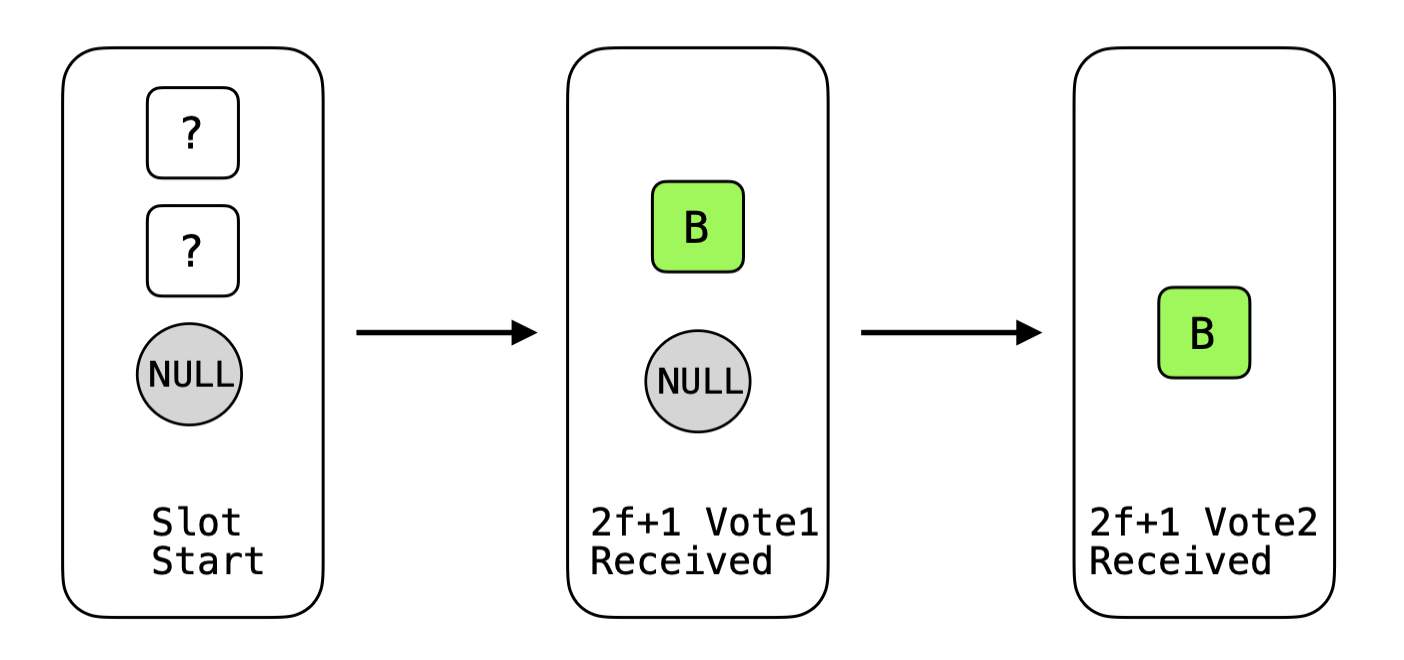

The second voting round is needed to maintain safety across slots. Intuitively, this is what it looks like from a validator's perspective:

- On slot start, before a quorum of

vote1is reached, a validator cannot be sure which block (if any) will be finalized. - After collecting

2f + 1vote1forB, the slot's outcome is "Bor empty" (no conflicting block can also collect2f + 1). - After collecting

2f + 1vote2forB,Bcannot be skipped in later slots, so it is safe to finalize. All honest validators will eventually learn this and finalizeBas well.

One Voting Round

We now know that with n = 3f + 1, we need the second voting round because 2f + 1 vote1 is not enough to decide between "block B" and "empty". A natural question is: if a validator gets more than 2f + 1 vote1 for a block in the first round, do the extra votes provide more certainty? The answer is yes: a validator can directly commit a block if it collects all votes (3f + 1) in the first round.

Suppose, in some slots, the Byzantine validators behave honestly (more on this later). A validator collects all 3f + 1 vote1 on block B. Then there cannot be another valid block that gathers quorum votes in that slot. We still need to ensure B cannot be skipped: any set of 2f + 1 timeout messages must intersect the 3f + 1 vote1 messages in at least f + 1 honest validators. This implies that at least f + 1 out of the 2f + 1 timeouts contain vote1(B), which is a strict majority. Therefore, the next leader (collecting 2f + 1 timeouts) is forced to extend B. So it is safe to finalize after receiving all 3f + 1 vote1 because the extra votes ensure the block won't be skipped. Conversely, receiving fewer (say 3f) vote1 is not enough, because it cannot guarantee that vote1(B) constitutes a majority within a quorum of timeout.

This yields a fast path that finalizes a block in just one voting round upon seeing 3f + 1 vote1. It is optimistic because it requires all f Byzantine validators to participate honestly in that slot. Any Byzantine validator can prevent the fast path by withholding its vote. We still need the second-round path as the default safe path.

If we want one-round finality without "optimism" about Byzantine participation, we need a way to avoid relying on Byzantine votes. It turns out the solution is quite straightforward: reducing the tolerated Byzantine fraction so that we can have more honest validators.

Assume n >= 3f + 1. Let validators move to the next slot after seeing n - f timeout. Let validators finalize a block after seeing n - f vote1 (the most votes we can guarantee without relying on Byzantine validators). Then the honest intersection of those vote1 and timeout sets is at least n - 3f (since (n-f) + (n-f) - n - f = n - 3f). To enforce that the block cannot be skipped, vote1 for that block within a quorum of timeout must be a strict majority:

This is saying that we can achieve stable one-round finality (without relying on Byzantine validators during synchrony) when n > 5f, i.e., when Byzantine validators are less than 20%!

Here's how it looks when n = 5f + 1:

- First vote (

vote1): after a validator sees the leader's proposalBand deems it valid, it broadcastsvote1(B). If a validator sees4f + 1vote1, it directly finalizes the block and moves to the next slot. - Timeout (

timeout): if a validator hasn't committed a block in a slot after a timeout, it broadcaststimeout. If the validator has sentvote1, it includes it:timeout(vote1). On seeing4f + 1timeoutmessages, a validator moves to the next slot.

If an honest validator committed a block, then it must have seen 4f + 1 vote1 for it. By quorum intersection, any set of 4f + 1 timeout messages must intersect any set of 4f + 1 vote1 messages in at least 2f + 1 honest validators (since (4f+1) + (4f+1) - (5f+1) - f = 2f+1), which is a strict majority. Thus, if the next leader collects 4f + 1 timeouts, more than half of them contain vote1(B), forcing the leader to extend B.

This is the intuition for how recent protocols like Alpenglow and Minimmit can achieve one-round finality with a 20% Byzantine threshold. This reduces three message rounds to two, which meaningfully reduces finality latency, especially with geographically distributed validators where network latency (~100ms for one round message) dominates. These protocols are also usually simpler to reason about because they avoid a second type of vote.

Note that we can still keep a two-round fallback in the consensus. The one-round and two-round paths can run concurrently. In that design, the quorum threshold for the two-round path can be x = 3f + 1 (i.e., 60%) so that two quorums intersect in at least one honest validator. This means the two-round path only needs 60% honest participation to reach finality. It can tolerate an additional 20% of honest nodes crashing while preserving safety and liveness. This is the intuition behind the "20% Byzantine + 20% crash" framing around Solana's Alpenglow design.

Between One Round and Two Rounds: Optimistic One-Round Finality

With a 33% Byzantine threshold we achieve finality with two vote rounds; with a 20% Byzantine threshold we achieve finality with one vote round. Now consider the intermediate case where the Byzantine threshold lies between 20% and 33%.

Assume n >= 3f + 1 and we use the same protocol structure as before. We know that the quorum for the two-round path is x > (n+f)/2. Suppose the one-round finalize threshold is y. To finalize in one round, we need enough vote1 such that more than half of the n-f timeout messages contain vote1 for that block. Using the same intersection reasoning:

As discussed above, we can run both paths concurrently: after the first round, if a validator collects x vote1, it broadcasts vote2 and continues collecting vote1. After collecting y vote1, it immediately finalizes the block.

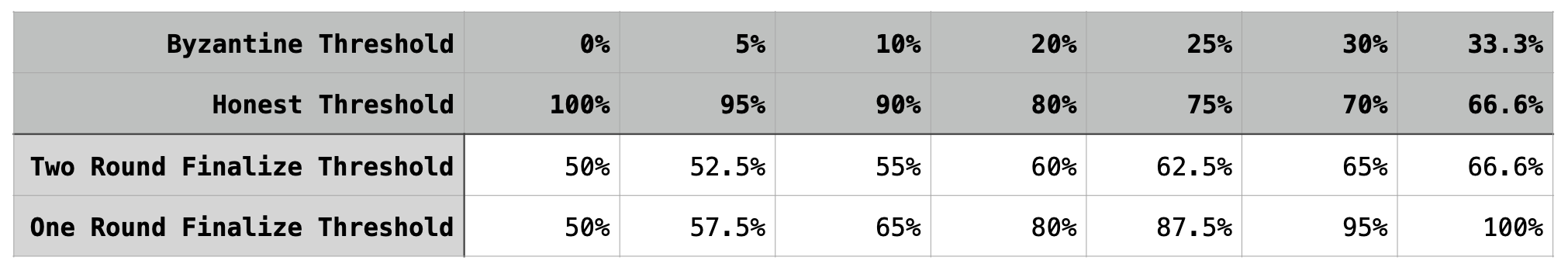

When the Byzantine threshold increases from 20% to 33%, the one-vote-round finality threshold y increases from 80% to 100%, which is always greater than the guaranteed honest participation n - f (from 80% to 66%). In that range, one-vote-round finality necessarily relies on some Byzantine validators' votes to trigger, so it becomes optimistic. The table below lists the finality thresholds under different Byzantine thresholds.

For example, when the Byzantine threshold is 30%, we can achieve two-vote-round finality with about 65% votes and one-vote-round finality with about 95% votes. This gives a feasible one-round fast path at the cost of decreasing the worst-case Byzantine threshold only from 33.3% to 30%.

This optimistic fast path idea has been studied in earlier work Fast Byzantine Consensus, and in more recently like Kudzu and Hydrangea. However, it has not seen widespread production adoption. One might think an optimistic fast path is less useful because "relying on Byzantine validators to do the right thing" sounds contradictory. However, actually it can be a practical way to reduce finality latency without sacrificing conservative worst-case safety, because:

- In PoS protocols, the Byzantine threshold is a worst-case security assumption: it specifies the maximum adversarial stake the protocol is designed to tolerate while still preserving safety and liveness. Protocols often choose a conservative bound (e.g., 1/3) as a defense-in-depth baseline, but that does not mean the system continuously operates at that bound. In practice, the effective adversarial stake is often lower, so it is plausible for a larger fraction of honest stake to participate in a given slot and unlock the fast path. In this sense, the fast path is "optimistic" about realized conditions being better than the worst-case bound.

- Byzantine behavior is not a static trait; it is a per-slot choice. In a long-running PoS blockchain, validators are economically incentivized to behave correctly and are typically penalized for detectable misbehavior (e.g., equivocation and inactivity). Sustained adversarial behavior across many consecutive slots can be costly and increases the risk of detection and punishment. As a result, even if the protocol must tolerate up to the worst-case amount of Byzantine stake, it is reasonable to expect that many slots exhibit milder adversarial behavior, making one-round optimistic finality more likely to trigger in steady state.

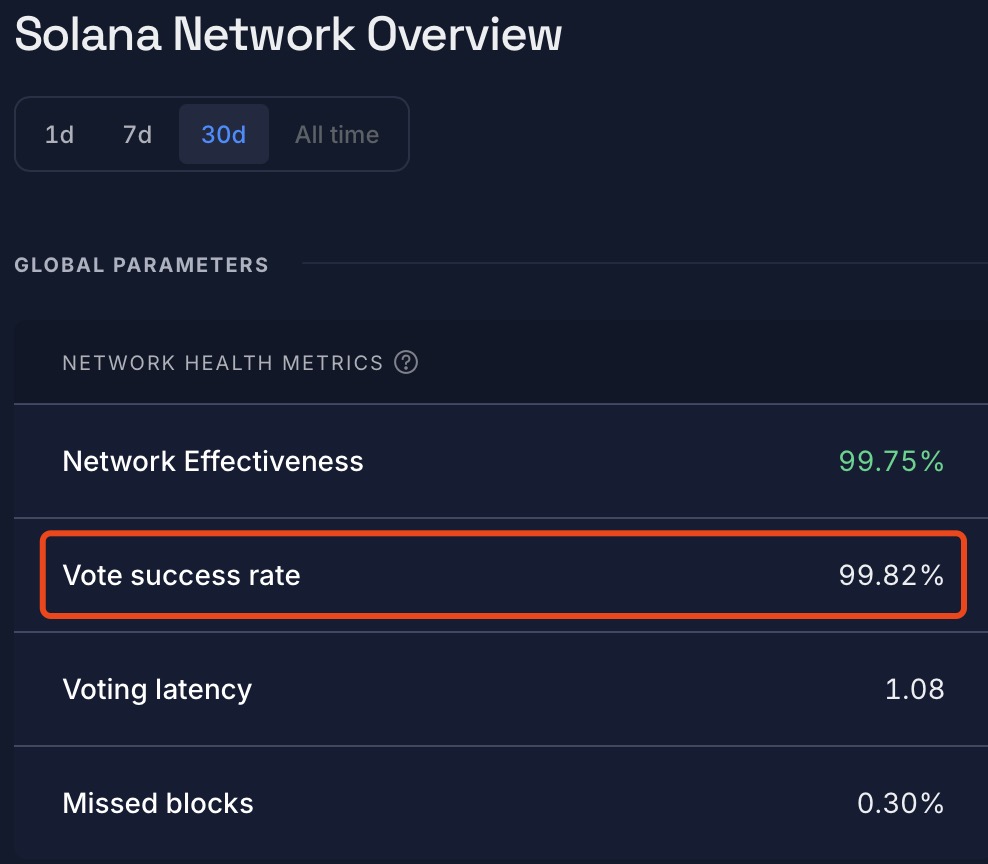

For example, both Ethereum and Solana have very high participation in practice (Ethereum participation ~99%+, Solana vote success rate ~99%+ on Rated), far better than the worst case assumption:

Ethereum currently uses two-vote-round-style finality, so blocks require two epochs (~12.8 min, each epoch is ~6.4 minutes) to finalize. With high vote rate in practice, it is technically feasible to target one-epoch finality by decreasing the Byzantine threshold to ~30% and adding an optimistic one-vote-round fast path.

The idea is to defend against the worst case while optimizing for the common case: two-round voting is the conservative baseline engineered to remain safe and live under worst-case network and adversarial assumptions. A one-round path can be used as an optimistic fast path layered on top. It can finalize earlier when a slot experiences better-than-worst-case conditions (e.g., high participation and limited adversarial disruption), while the two-round path remains the fallback that preserves the original resilience guarantees.

Conclusion

Most PoS blockchains assume a 33% Byzantine threshold because it is the classical upper bound for partially synchronous BFT consensus. In that setting, two vote rounds are needed to ensure safety across slots. Some recent BFT protocols assume a 20% Byzantine threshold to achieve one-vote-round finality, reducing three message rounds to two. Between 20% and 33%, optimistic one-vote-round finality is possible: it requires more votes than the guaranteed honest threshold and therefore depends on (some) Byzantine validators not disrupting a given slot. Still, as a fast path layered on top of a conservative baseline, it can reduce finality latency in practice without sacrificing worst-case safety. It would be interesting to see more blockchains explore this design space.